This weekend (Friday and Saturday) I had the pleasure of taking a class at the Pacific Northwest College of Art in Portland: CED 312-1,

Graphic Novel: Narrative and Persuasion, taught by

Scott McCloud.

Essentially, this a sixteen-hour lecture and lab version of the content from

Making Comics, McCloud's latest book, a primer on how narrative works in comics

(1). Although I have read and re-read the book (along with

Understanding Comics), and use a lot of McCloud's principles and models when discussing comics in the classroom, I found the experience of working directly with McCloud very valuable. While I can't say there were revelations and new insights to be gained from the class for someone familiar with McCloud's written works, the practical application of techniques and the peer and instructor critique added a depth to my understanding.

The student made up a mixed bag. Some were matriculated students at PNCA taking the class for credit; for some people this was the end of a week-long course in graphic novels that had included other classes (one taught by Trina Robbins); some, like me, were just taking Scott's segment. Some were already comics creators or wanted to be, but that was certainly not universal: one fellow was looking at all forms of narrative to find an idiom in which to present his memoirs and another guy was a mediator looking for new models of creative thinking. The class of thirty or so was split about evenly between men and women; the youngest student was a 17-year-old girl and there were at least two men in their sixties, with the rest of us spreading out between the extremes.

Scott started the class with a slide show that outlined the typical steps in the creation of a comics narrative - plot outline to script to layout to pencils to inks - and then explained how any or all of them could be omitted or truncated.

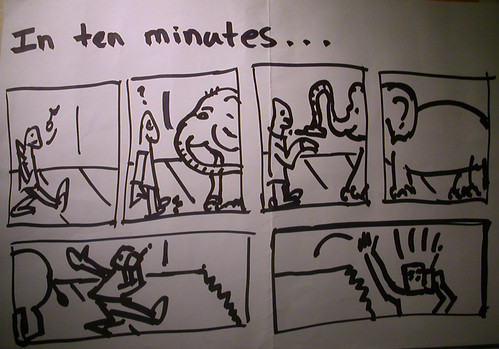

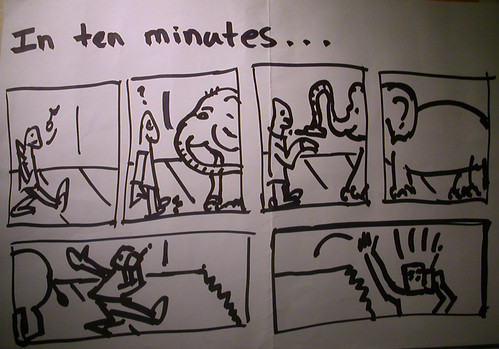

This led into an exercise that replicated the guy-finds-a-key story in Making Comics (page 11): Scott gave us a short story summary

(2) and we had ten minutes to create a strip that told the story as we understood it. Students took from three to fourteen panels to compose the narrative;

I took five (or six, depending on how you count) - how many would you use?

As we critiqued each and every strip in panel number order, we could see clearly how the tension between economy and detail worked itself out in each person's creative act and the choices they made

(3).

"Choices" is, of course, Scott's overarching conceit for the creative process: he breaks down comics creation into Choice of Moment, Choice of Frame, Choice of Image, Choice of Word, and Choice of Flow. The panel count, for example, is one aspect of a creator's Choice of Moment: how many are necessary to tell the story you want to tell?

The class was not designed to go into much detail regarding Choice of Flow, which is concerned with page-level layouts and alternate web layouts

(4), but we continued with more lecture on Choice of Moment (including a review of the six types of panel transition

(5)) and moved into talking about Choice of Frame and the balance between clarity and intensity. We looked at stories by Moebius, Drooker and Huizenga to illustrate the concepts being discussed, and it tuned out that reading comics on a big screen worked surprisingly well.

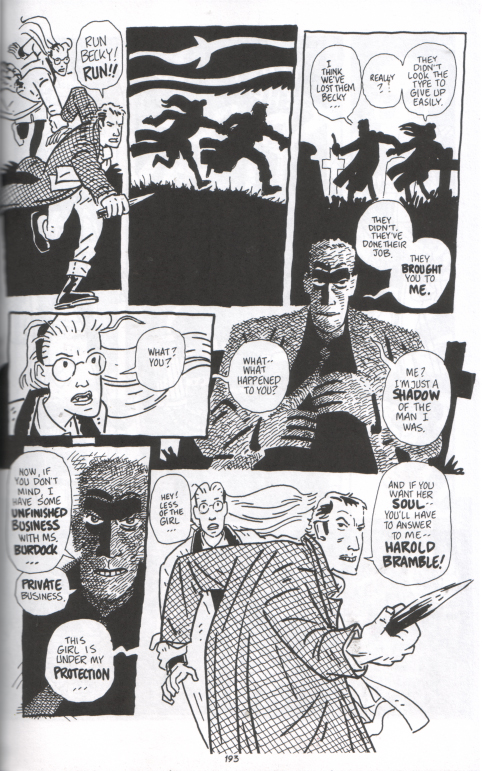

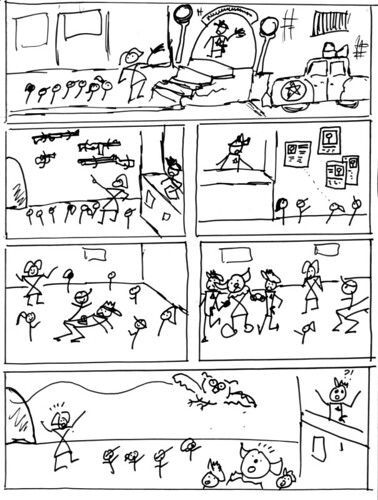

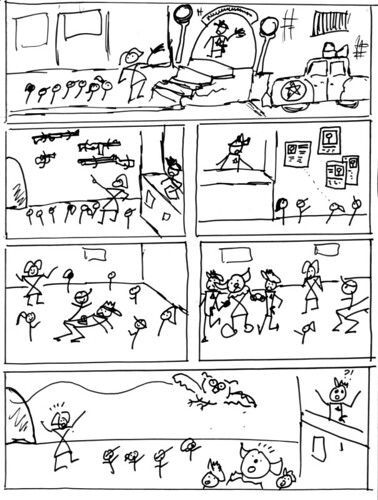

We then moved into the studio for some extended exercises, the first of which was rendering (in twenty minutes) a six-panel script that deliberately included disjunctive elements. This narrative quirk compelled a high degree of clarity on the part of the creator, since logical extrapolation would not help get a viewer to the message. This strip by a classmate

(6) is a good illustration:

The representation of the supermarket activities in the first three panels is spot on and entirely clear; the introduction of "a rhino falls from the ceiling" in panel four works less successfully, since the rhino looks a bit like a pig with a mask on, and without any contextual clues, the closure that gives a reader "rhino" was not certain. In this case, it did not seem to be a question of Choice of Moment (that was specified in the script) or Choice of Frame (it seems fitting), but just Choice of Image (and more practically, no chance for a reference image).

In the interest of full disclosure, here's my strip for the same assignment. I had a slightly more complicated script and executed it with much less skill:

We all completed different strips like these and reviewed them in small groups; each group selected one strip for a larger discussion. The relative clarity (or lack of it) as a result of creator choices was apparent.

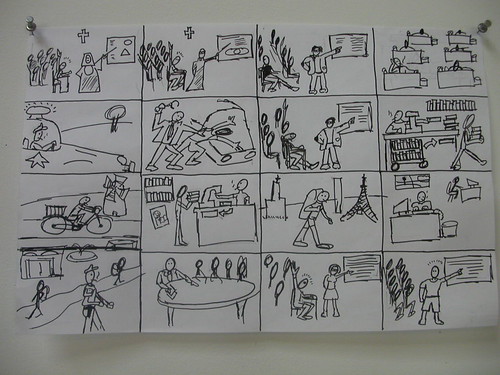

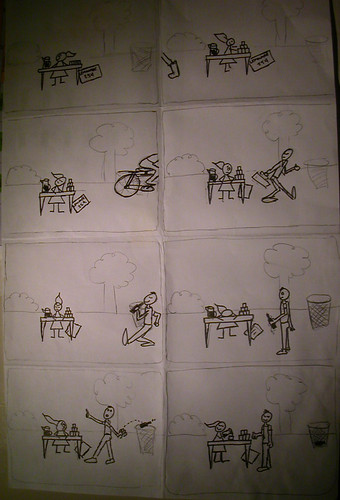

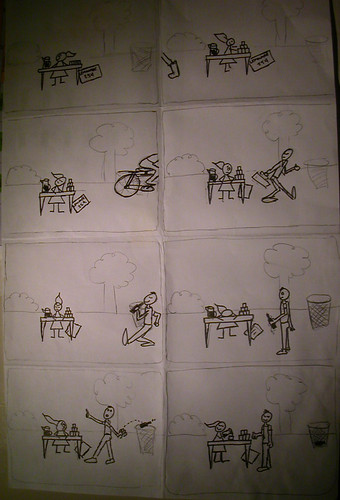

We followed this activity up with an even longer strip: the instructions were to use a straightforward four-by-four, sixteen panel grid to create a narrative based on your own life. This became a two-level exercise for me. On the one hand, it was a more in-depth look at the same kind of choices as we were making in the short strip: since the details of our lives were personal and peculiar, clarity of presentation was extremely important so the specific details of the narrative could be understood.

The second level, however, resonated with me more as a teacher of writing: many people began by depicting their birth and ended with coming to the class we were in, and were dissatisfied with their attempt to accurately depict their entire lives in just sixteen panels. Very few students chose to move to the specific rather than the general and to tell the story of just one aspect of their lives. This approach, which I took (showing only education and employment) might give a narrative which is less comprehensive but more solid, with a clearer narrative arc. Here's the strip:

In any case, the exercise stretched people's creativity (we had only an hour and twenty minutes for the whole thing), and the critique - Scott went over every piece in detail - took the end of Friday and the first hour of Saturday, and covered Moment, Frame, and Image.

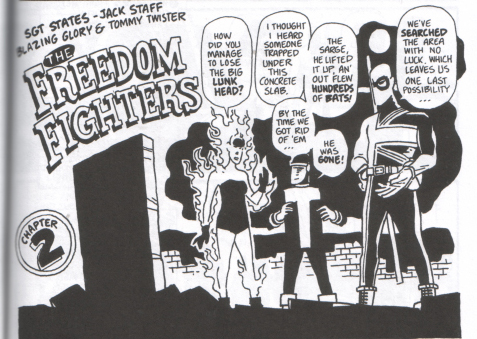

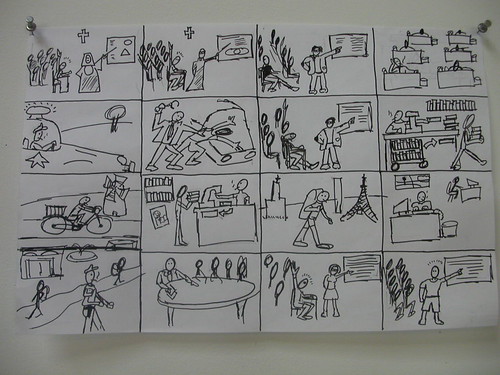

Saturday morning continued with a lecture on character design as an example of Choice of Image (with what seemed to be a slight digression into the "shape of storytelling"

(7)). Then the presentation turned into more of an art class, with Scott demonstrating the look of the six emotional primaries - anger, fear, disgust, joy, sadness, and surprise - and showing how the secondary, more complex emotions were combinations of the physical elements that make up these primaries. Much of Saturday was filled with studio exercises in communicating different emotions through facial expression and body language. My attempts at illustrating these gradations were not successful enough to add anything to this account, but you can see some other versions on the wall in this photo.

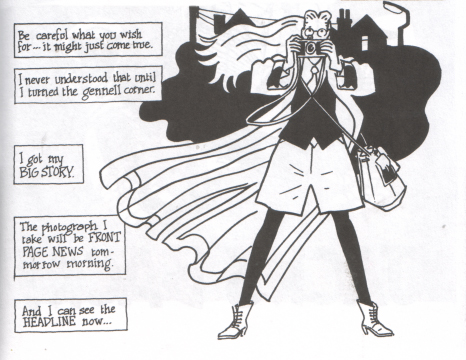

Our final project was to create a fully developed narrative strip (in ninety minutes) that demonstrated our understanding of the Choices. For better or worse, this is as good

(8) as my understanding got:

Overall, I have to say that I was impressed with Scott McCloud as a classroom instructor. He is clear, personable, and accessible, and presents the material in a manner that models collaboration with the student rather than preaching. For me, the class was more review than enlightenment, but it was a rich and textured review that increased my confidence with the material. Unfortunately, due to technical glitches, Scott was unable to present his lecture on Choice of Word, the segment that might have been of the most interest to me, but I still got a lot out of the entire experience, and took away some ideas for my classes.

If you ever have a chance to take one of these classes, do it.

(1) Notwithstanding Neil Cohn's recent post on nomenclature, I continue to use comics as the shorthand for sequential art, however we may wind up ultimately defining it.

(1) Notwithstanding Neil Cohn's recent post on nomenclature, I continue to use comics as the shorthand for sequential art, however we may wind up ultimately defining it.

(2) For the record, the summary was A man walks down a sidewalk, whistling. He meets an elephant, who gives him a cell phone. He thanks the elephant and continues walking, talking on the cell phone. He then falls off a cliff.

(3) This tension reminds me of an approach to judging the best length of a written piece: use as few words as you can and as many as you need to. (This is itself a paraphrase of advice I heard from a driver's ed instructor: drive as fast as you can and as slow as you have to.)

(4) Although that didn't stop me from responding to the latest post on the wonderful Remedial Comics.

(5) Moment-to-moment, action-to-action, subject-to-subject, scene-to-scene, aspect-to-aspect, and non sequitor.

(6) For the record, I don't think anyone in the class was more fluent in the language of comics than this creator.

(7) McCloud held that you can't have a story unless someone wants something, and that the three templates are "desire achieved and then rejected" (Wizard of Oz), "desire denied and then rejected" (It's a Wonderful Life), and "desire achieved" (The Little Mermaid). I had not encountered this model before.

(8) Scott took this strip apart kindly but quite thoroughly and pointed out lots of places for improvement. He also didn't like that the "achievement of desire" came about more through the kindness of a stranger than the girl's own effort, which seems a valid criticism.

Note: The post title comes from McCloud's mantra all weekend.